We are all motivated to eat. This is a basic function of survival. In fact, our brains are equipped with an ancient motivational system that ensures we are driven subconsciously to hunt and gather (“go and get”) food, particularly calorie-dense foods. This ancient system can lead to overeating and weight gain in our modern food environment.

The Why, Who, What, When, How and Where of Anti-Obesity Medications

Earlier modules have described the risk of overweight and obesity to be a real, genetically conferred, brain-centred, progressive, chronic disease. Earlier modules have also stated that real, safe and effective treatments exist for this condition. The first pillar of overweight and obesity treatment is behavioural therapy. The second treatment pillar is anti-obesity medications (AOMs). The third treatment pillar is surgery. The focus of this module is on anti-obesity medications.

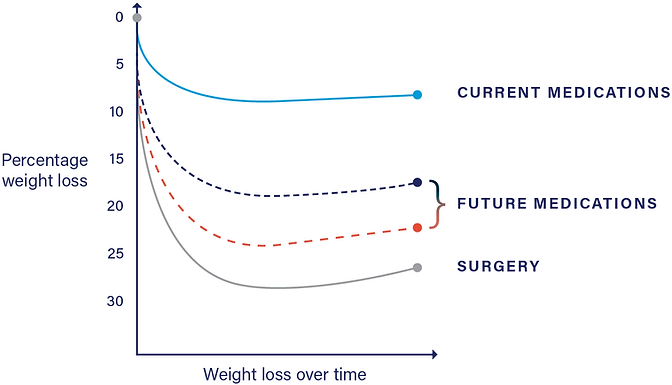

Today, safe and effective AOMs exist as adjunct to behavioural therapy. You can anticipate that progressively more effective AOMs will play a central role in obesity treatment, much like medications do with hypertension, diabetes, asthma and arthritis medications. It is anticipated that AOMs will eventually compete with bariatric surgery in weight loss and health outcomes.

In Canada, obesity surgery includes the sleeve gastrectomy, the gastric bypass or the duodenal switch. You may think that the weight loss effects of these procedures take place at the level of the abdomen, however, perhaps surprisingly, the majority of the weight loss effects of these procedures is accomplished via a strong influence on all three layers of the appetite system as described here in the case of gastric bypass.

Why would anyone need medication or surgery in the first place?

In earlier modules you learned that weight is regulated within your brain with a three-level appetite system. You will have learned in the restraint module that behavioural therapy targets the third level, the executive system. To be specific, behavioural therapy empowers you with skills that awaken your sleepy executive system just when he or she is most needed. Your executive system is where thinking happens, and you have access to your thinking.

It is different for the other two levels of your appetite system. You do not have access to these two levels, yet, as you have learned, these two levels are critical in regulating your weight. Specifically, they defend against weight loss and drive WANTING. This defense, meant to promote weight gain, comes in the form of increased appetite and decreased metabolic rate. We learn here how hormonal changes signal the brain to defend against weight loss by increasing appetite, and we see here how this increase promotes slowing weight loss and the risk of weight regain.

While you don’t have access to these two layers of the brain, AOMs and surgery do.

One way to think about the role of AOMs and surgery is to consider them as defences against the defence.

Both Liraglutide 3.0 and Naltrexone/Buproprion act on the brain and directly influence activity at the level of the homeostatic system (GATEKEEPER) and the motivational (GO-GETTER) system. Orlistat, an older medication, does not work on the brain and will not be further discussed in this document. Certainly, ask your physician about Orlistat if you are interested in hearing more.

MEDICATION AND THE GATEKEEPER

Liraglutide 3.0, as shown here, and Naltrexone/Buproprion, shown here, directly influence the GATEKEEPER, specifically landing at the gate to the GATEKEEPER, the arcuate nucleus. This stimulates fullness and lowers appetite, countering the upward pressure effect of weight loss! This is where most of the body’s appetite hormones act to signal the brain.

MEDICATION AND THE GOGETTER

The central role of WANTING has been established in the WANTING module.

WANTING drives excessive calorie intake, and excessive calorie intake drives weight gain (and confounds weight loss). Both Liraglutide 3.0 and Naltrexone/Bupropion reduce WANTING via their influence on the GOGETTER.

One way to measure WANTING is via the validated Control of Eating Questionnaire (COEQ) here, which measures the strength of WANTING. Here, a glp-1 analogue called Semaglutide 2.4 mg, a once-weekly medication which is currently under consideration by the FDA as a new AOM, significantly lowers scores on the COEQ. Here, Naltrexone/ Bupropion also reduce scores on the COEQ.

Another potential way to measure WANTING is functional MRI studies. Here, Liraglutide 3.0 treatment, and here, Naltrexone/Bupropion treatment are associated with fMRI changes consistent with a reduced WANTING response in the GOGETTER.

Outcomes

Clinical trials are conducted to determine the safety and efficacy of an AOM.

Here, Liraglutide 3.0, combined with lifestyle counseling, resulted in an 8.0% weight loss at one year.

Here, naltrexone/bupropion, combined with lifestyle counseling, was associated with weight loss of 6.1% at one year.

Responders to AOMs are broken into two categories

-

Early responders: Someone who, upon starting an AOM, loses greater than or equal to 5% of body weight within 12–16 weeks.

-

Non-early responders: Those that do not lose 5% or more at 12-16 weeks.

Not responding to one AOM does not mean the same person would not respond to another AOM.

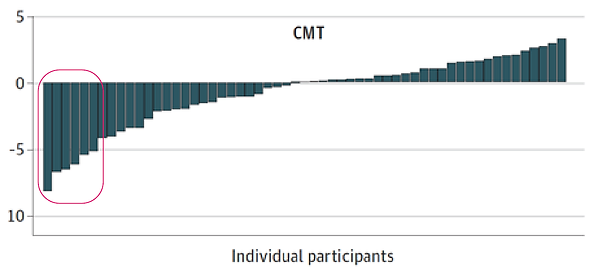

So what are the outcomes if we only consider those who responded to the AOM and would be likely to continue on an AOM? Here, early responders to Naltrexone/Bupropion had lost an average of 12% of their body weight at one year. Here, early responders to Liraglutide 3.0 mg lost an average 10.8% at one year. Here, the anticipated AOM Semaglutide 2.4mg showed an average weight loss of 17.4% when considering all subjects after 68 weeks. What about the early responder numbers from this study? This has not been calculated yet but you can assume it will be significantly more than 17.4%.

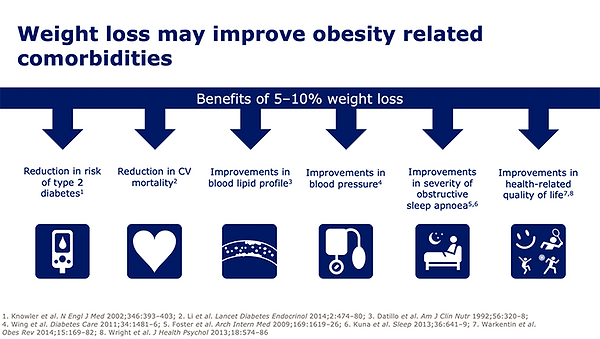

Treatment with these AOMs is also associated with significant improvements in weight-related conditions such as high cholesterol, blood pressure and blood sugars.

WHO SHOULD CONSIDER MEDICATION?

You have learned that many people living with overweight or obesity have internalized the pervasive shame and blame narrative and believe that theirs is a moral failure, and a failure in motivation and strength. As described in the internalized weight bias module, the opposite is true: overweight and obesity is a consequence of a primarily genetically conferred, central nervous system-based, environmentally influenced, progressive, medical condition. In this alternative narrative, medication is seen as a treatment for a real condition. And so, the individual who should consider medication is the individual who has been invited to consider medication as an effective treatment for a real condition. The decision to take or not take an AOM is yours. A clinician’s role is to invite and inform you as to the benefits, risks and appropriateness of medication in your treatment. The rest is up to you.

This next point is important. Ideally, AOM use is combined with behavioural therapy. Medication is often described as an adjunct to behavioural therapy and so, the individual who should consider medication is the individual who has been invited to consider behavioural therapy. Ideally, this behavioural therapy is provided by a practitioner certified in overweight and obesity treatment. Certifications in obesity medicine are becoming much more common.

When discussing who should consider AOM use, it is important to describe the concept of indications and contraindications—literally the things that would make you an appropriate candidate for treatment, and the things that would preclude you from using the medication.

Indications:

-

A BMI of 30 or above, or

-

A BMI of 27 and above if associated with comorbidity such as hypertension, diabetes, elevated cholesterol, sleep apnea, and osteoarthritis.

The reasoning here is that these conditions are strongly associated with weight and that weight loss is strongly associated with improvements in these conditions. All AOMs in Canada are formally described as “an adjunct to reduced calorie diet and increased physical activity for chronic weight management.”

Contraindications:

Each medication has its own list of contraindications and you should learn these from your prescribing doctor.

WHAT MEDICATION SHOULD YOU CONSIDER?

All three available AOMs in Canada: Orlistat, Liraglutide 3.0 and Naltrexone/Bupropion are safe and effective; speak to your physician for a full review. Both Liraglutide 3.0 and Naltrexone/Bupropion are well-tolerated, and studies show discontinuation due to side effects is rare.

Which medication would be most effective for you? Before trying a medication, there is no way of knowing or predicting your response. When it comes to medication (or behavioural therapy or surgery), there are responders and there are non-responders.

WHEN WITHIN TREATMENT, SHOULD YOU CONSIDER MEDICATION?

Behavioural treatment is the foundation of the treatments of overweight and obesity. When considering AOM use, consider the following four options:

Treatment Exists

Internalized bias is also countered by learning that effective long-term treatment exists for overweight and obesity. The three treatments are behavioural intervention, medication and surgery.

Treatment Exists

Internalized bias is also countered by learning that effective long-term treatment exists for overweight and obesity. The three treatments are behavioural intervention, medication and surgery.

OPTION 1 is to not use an AOM at all. With expert behavioural treatment, 33% of individuals will lose at least 10 % of their body weight at the end of one year of treatment. This group is considered responders to a behavioural treatment. With less than expert behavioural treatment, you can still expect a significant number of responders. Behavioural therapy alone can be effective for a significant number of individuals.

OPTION 2sees you starting medication in concert with the initiation of behavioural therapy. This is a reasonable option, and if you are a responder, you will likely lose significantly more weight than with behavioural therapy alone.

OPTION 3 is to consider adding an AOM if behavioural therapy alone is associated with a non-response. Again, not every individual is a significant responder to behavioural therapy. The addition of an AOM in this situation can dramatically improve your weight loss and even “open” an ability to excel at behavioural therapy.

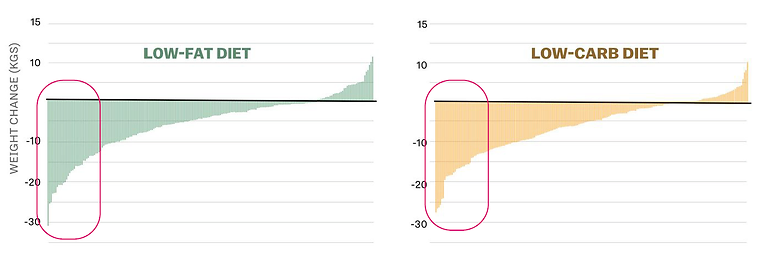

OPTION 4 would be a consideration if, with behavioural therapy alone, your BEST WEIGHT is not associated with best health and quality of life. In the expectations module it is clearly described that all weight loss curves have a characteristic shape, with successful weight loss slowing and slowing and eventually flattening at one’s BEST WEIGHT (formerly called the plateau). If your BEST WEIGHT is not associated with best health and quality of life with behavioural therapy alone, the addition of an AOM can significantly further weight loss, resulting in another curve the same shape but landing further down.

Again, WHEN to initiate medication can be discussed in consultation with a physician, but the decision of if and when to initiate an AOM is ultimately yours.

Initiating an AOM begins with you learning how the medication works and being advised in detail regarding any risks and side effects. You would learn about a stepwise dose escalation that you should be personally in control of. The dose escalation can help you minimize side effects and consider the lowest effective dose for the AOM. It will be explained to you that because the disease of overweight and obesity is life-long, the treatment is also considered life-long. Prescription of an AOM is envisioned to be a long-term treatment, not a short-term one. Having said that, some patients may consider, at some point, a trial of coming off the AOM and deciding for themselves on a weight management path with or without medication. After initiating an AOM, you should be assessed for: 1) a measured appetite response, 2) reported weight (if you wish), and 3) improvements in quality of life and health factors such as bloodwork and measurement of disease risk factors.

WHERE COULD YOU BE PRESCRIBED AN AOM?

This is important. This author anticipates a time in the near future when primary care doctors globally will have confidence and competence in treating patients with overweight or obesity, providing a behavioural intervention and possibly medication as an addition to treatment. You may need to be an advocate for yourself based on the medical system you are in. You have learned from the Internalized Weight Bias Module that many, including health care practitioners, still think of overweight and obesity as a matter of willpower, diet and exercise: “eat less, move more.” This means that you may be faced with overcoming bias and discrimination in order to gain access to credible, ethical, expert and effective treatment. Also, when discussing where you may access treatment, a modern note: There is every reason to believe that effective overweight and obesity treatment can be provided remotely. Please access the upcoming remote treatment module.