We are all motivated to eat. This is a basic function of survival. In fact, our brains are equipped with an ancient motivational system that ensures we are driven subconsciously to hunt and gather (“go and get”) food, particularly calorie-dense foods. This ancient system can lead to overeating and weight gain in our modern food environment.

Wanting – the Motivation to GO AND GET Calories

This section can be thought of as the beginning of treatment. We have already established that excessive calorie intake drives weight gain and confounds weight loss. But what drives excessive calorie intake? You might think the answer is complicated but it isn’t.

The answer lies in the middle layer of the appetite system. The appetite system has three layers, with the middle layer best known as the motivational system. The human appetite system evolved from living in an environment where calories were often scarce and finding food involved work, hence the motivation to GO AND GET. The prevailing understanding of how and why obesity happens is that this ancient system has collided with the modern food environment; this ultra-processed, sugar, fat and salt added, big-portioned, everywhere, anytime, aggressively advertised, delivered-right-to-your-front-door food environment. It is also important to note that even the overabundance of healthy food in our current food environment can drive the overconsumption of calories and contribute to weight gain. The assumption that weight gain, overweight and obesity are always a result of unhealthy and/or highly processed junk and fast food is both flawed and highly stigmatizing.

Ivan Pavlov was a Russian scientist in the early 1900s. You may recall his famous experiment where dogs salivated to the sound of a bell. By repeatedly pairing the bell with the delivery of tasty sausage powder to dogs, the bell alone eventually became a powerful trigger of salivation (i.e. WANTING) in the dogs. Salivation is a reflexive and automatic response to the anticipation of food, an early phase of digestion, and it was triggered by a bell! Pavlov even showed that salivation (i.e. WANTING) was triggered in the absence of hunger by ringing the bell after the dogs had eaten been fed. By mapping out your High-Risk Times, you are discovering your “bell”, the settings and cues that have been paired with tasty foods or an abundance of food repeatedly and are now powerful triggers of WANTING.

What is the outcome of this collision? Abundant and energy-dense foods ensured survival in our former environment. When we eat abundant and/or tasty food, it is tasty, sensed in our mouth and digestive tract and a signal is sent to our brain that we are eating survival-imperative foods. As the food and signals collide with our motivation system, we learn to associate the environmental cues around us with these foods. This is called associative learning or Pavlovian learning (see highlight on Pavlovian learning). After repeated associations, the environmental cues themselves gain the power to generate WANTING and make us GO AND GET.

WANTING is also known as a desire, urge, impulse, craving, attention bias or incentive motivation and is often described as a wave because of its property of rising, cresting and falling. WANTING resides completely in the subconscious. WANTING occurs often without conscious awareness and is the driver of overeating. For example, if abundant and/or tasty food is paired enough times with the setting of night-time-couch-TV-dark windows-pre bedtime, eventually this setting itself reflexively and subconsciously generates WANTING and makes us GO AND GET. If the setting of walking through the door to your home at the end of the day —the jacket off, bag down walk into kitchen-—is repeatedly associated with pre dinner tasty energy-dense food and/or drink, eventually the simple act of walking in your door at the end of the day gains the power to generate reflexive WANTING for food and/or drink. In these two scenarios, the times of day and environments become established as High-Risk Times (HRTs). WANTING is different from hunger, but both are real and powerful physiological responses. Hunger resulting from going too long without food also triggers WANTING, but WANTING commonly happens without hunger and these are the times individuals take in more calories than they need because WANTING drives excessive calorie intake.

Seventy percent of the likelihood of struggling with weight in one’s lifetime is inherited. Over 1000 genes so far have been associated with overweight and obesity and a majority of these genes are expressed in the central nervous system (brain), where our weight, appetite, and metabolism are regulated. The strength of this motivational drive is highly heritable. Stronger WANTING is considered a key heritable risk to weight struggles. WANTING resides completely in the subconscious; we have no access to the motivational system. WANTING is a neurological reflexive brain event that is mediated by a chemical called dopamine and can be clearly seen on MRI as this area of the brain lights up in response to food cues.

Characterizing WANTING

The tools in this section will help you learn the cues, places, times and settings where you now most commonly, reflexively and subconsciously, experience wanting. It is at these High-Risk Times (HRTs) that extra calories are most likely to be consumed. It is here that the reduced calories that can lead to weight loss are most likely to be found. What are the cues and settings that have, in your life, been repeatedly associated with tasty or abundant calories? Understanding and managing Wanting is significantly associated with improved outcomes.

Change to bell icon.

Mapping WANTING and your High-Risk Times

Your WANTING map contains the cues, places, times and settings that have repeatedly been associated with abundant and/or tasty food or drink in the past, and where you now reflexively and subconsciously experience WANTING. What are these cues?

Mapping determines your High-Risk Times (HRTs). Please consider the following exercise to help you identify your HRTs.

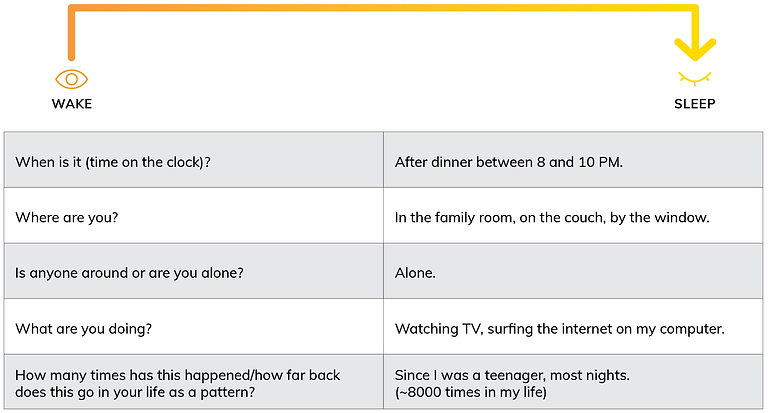

Let’s say that this is the timeline of your day. At the beginning of the line is when you wake up and the end of the line is when you go to sleep. Is there anywhere along this line where you would consider yourself, with any regularity, more at risk of eating more food (or drink) or less healthy food?

Urge Surfing

One way to gain a better understanding of WANTING is the exercise of urge surfing, or riding the wave of WANTING. This exercise may help you recognize and accept WANTING as an experience that you cannot necessarily stop or control, but that just happens in a patterned way.

Consider the following steps to guide you through the exercise of urge surfing:

1. Recognize when you are experiencing WANTING and acknowledge it for what it is. Try saying it aloud. (e.g. “I’m really WANTING something sweet / salty / crunchy / tasty right now. I know what this is,” or “I am experiencing WANTING / a craving right now.”)

2. Be open to the experience of WANTING. Try not to suppress or fight it. Try not to judge it or label it as good or bad, right or wrong. Simply accept it as something that is happening to you in a moment of time.

3. Observe the experience of WANTING:

-

Where do you physically feel it in your body?

-

How intense is it? (Score out of 10, 1 = very weak, 10 = very strong)

-

What thoughts are going through your mind (screening for permission thinking)?

-

What feelings are you experiencing?

-

Consider surfing the urge and see if the intensity of it changes over time – after 5 minutes, after 10 minutes, after 15 minutes.

-

Does it subside and if so, how long does it take?

-

If it subsides, does it come back?

Understanding WANTING and its significant impact on eating behaviors, calorie consumption and weight is an important first step. In the treatment modules to come, you will learn behavioral and cognitive techniques and strategies to help you avoid WANTING if possible, minimize the intensity of WANTING, and manage WANTING when it occurs. Understanding and managing WANTING is significantly associated with improved weight loss outcomes.

Leave a Reply